The Peach, 1981 Gouache and ink on paper. 11 x 11”

CHING HO CHENG

1946 – 1989

Infinity in a Peach Pit: My Brother’s Quest for the Eternal

Ching Ho Cheng was born in 1946 to a family of government officials. His father, Paifong Robert Cheng, held the diplomatic post representing the Republic of China in Havana, Cuba during the 1940s, his mother Rosita Yufan Cheng was a fashion designer. Ching’s great aunt Soumay Cheng (aka Madame Wei Tao Ming), the matriarch of his family, is credited for saving China’s most sacred province Shandong from being relinquished at the signing of the Treaty of Versailles. The new regime emerging in China under Mao Zedong made it impossible for the Cheng Family to return to their country. When they arrived in 1950, Ching was one of 105 Chinese immigrants who entered the U.S. under the quota of the Magnuson Act (1943-1965). As a result, this generation of Chinese American artists are largely absent from our historical archives.

Although Ching Ho was his first name, he was known as “Ching.” Ching grew up in Queens and began winning art competitions in junior high school. When he won first place for a portrait of his sister, the Long Island Press featured him on the front page of the newspaper. This was the beginning of his interest in art, he spent his summers studying at the Arts Students League before matriculating to the Cooper Union School of Art. His college years were marked by the Vietnam War and its draft. The war was widely protested and in 1967 over 100,000 demonstrators attended a rally against the war at the Lincoln Memorial in DC. This was the turning point for Ching, at which he found solace in Taoism that would become predominant in his life and open his mind to the metaphysical. It became a subtle, but noticeable, presence in his entire body of work.

Ching lived in the East Village during the 1960s Hippie movement and in Soho during the 70s. Eventually, he landed at the Chelsea Hotel where the manager Stanley Bard would rent Ching different apartments; often he would move into larger studios to accommodate larger paintings. Stanley also allowed artists to pay their rent late which made it very attractive to artists. Ching was extremely disciplined, one winter he worked in a Soho loft that had no heat, he managed to paint 7 hours a day wearing his fingerless gloves. As far back as I can remember, my brother simply loved to paint; it meant everything to him, and it was obvious he would become an artist. Downtown was the creative mecca of New York in those days. Ching would meet the most interesting artists and friends that were both American and international at Max’s Kansas City (famous restaurant/bar for artists) and the Chelsea Hotel. He was a progressive thinker, and his friends were eclectic and avant-garde. It was the perfect venue to discuss your work and exchange ideas. Scores of projects originated from hanging out at Max’s and the Chelsea.

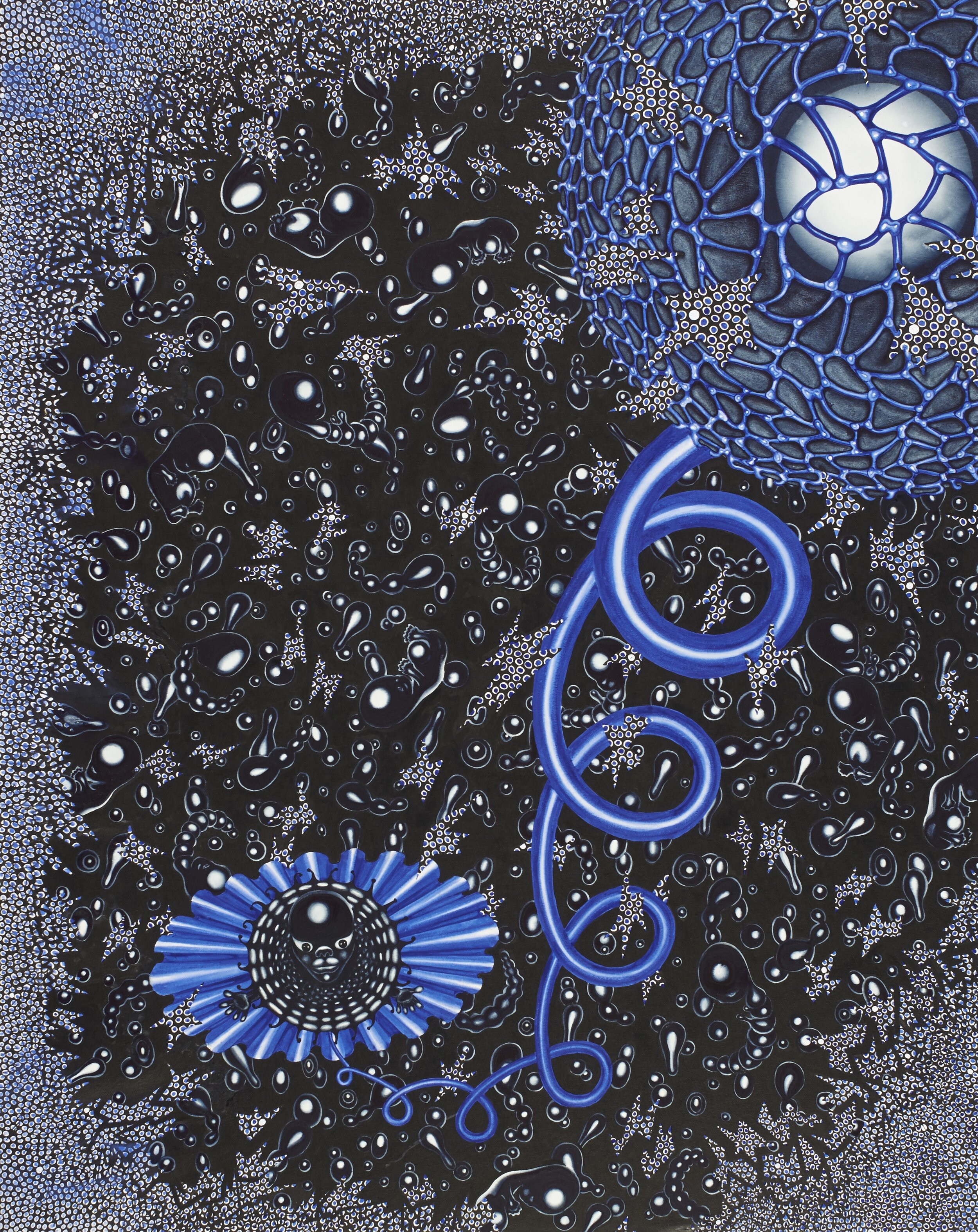

Ching Ho Cheng worked primarily on paper. His work is divided into four distinct periods, the Psychedelics, Gouache, Torn Works, and Alchemical Works. Although they appear completely different in painting style, there is a symbiotic relationship that connects all four periods. After graduating from the Cooper Union School of Art he began his dynamic psychedelic series using gouache and ink as a medium. He was greatly inspired by the spiritual symbolism in Tibetan art. The use of the mandala in his “X Triptych” depicts eight rings (Panel II), each one forming Ching’s own guiding principles and beliefs. The blue cord in Panel III of the triptych that connects to the astral baby is the thread of life to the next chakra. The same cord reappears in “Glossolalia” and “Angel Head” as well, it is also known as the silver cord which connects your body to the next realm. Eventually upon death the threads break, and you move on into the astral plane. In “Chemical Garden” the paisley form represents fertility and eternity, its origins dating back 2000 years. Ching was on a quest to paint the essence of life. He would complete every series of his work with a master painting. It is the culmination of all previous paintings in that series. “The Astral Theatre” is the master work of the psychedelics.

X Triptych, 1970 Panel II Gouache and ink on rag board. 30 x 30”

X Triptych, 1970 Panel III Gouache and ink on rag board. 30 x 24”

In his next series Ching was ready to paint without “explosions” as he put it. The psychedelics were extremely complex in composition and execution, often taking months to complete, but he was primed to discover an opposing style of implementation. He wished to attain the “subtlety” in his painting that he admired in Picasso’s Bull. Thus, the Gouache Works became his second series in this artistic journey. Here you will see the everyday objects he painted - a peach, a light bulb, a match, a palmetto leaf, these are Ching’s still lifes. They are imbued with metaphysical attributes that he hoped the viewer would experience through his work. The peach is a common symbol for longevity and immortality in Chinese philosophy. A palmetto leaf signifies peace and eternal life in the Mediterranean region. In many spiritual and religious practices around the world the “light” serves as a symbol for “hope and happiness.” As Ching approached the end of the series, the master work evolved into either a shadow or luminous white light painted on paper. There is a transcendental element in his work, a pureness that I can only describe as peace.

Untitled, 1980 Window Series Gouache on rag board. 30 x 28”

As a general rule, Ching rarely kept any of his work that he felt did not meet his level of perfection. Instead, he would simply tear it to pieces. I remember being shocked each time I would witness this. He could easily destroy something that he might have worked on for weeks. It was this act alone that led him to his third phase of his work: The Torn Works. This series which is bold and striking incorporates various geometric shapes such as a vortex, a rectangle, or the UFO disc. These particular forms symbolize spiritual beliefs in the transcendental world. Ching would visit sacred places like Stonehenge and the pyramids where the vortex exists. He believed these vortexes emanated certain frequencies that could heal or awaken the higher consciousness. His metaphysical beliefs continue in this series but clearly evolve from his earlier works in that they become abstract.

It was in the 1980’s that Ching tragically began losing his friends to the AIDS epidemic. During this period, he had psychic readings with Frank Andrews, a well-known celebrity psychic. It was through these readings that Frank spoke of the “certainty of blue” to Ching. His interpretation was to implement blue for the spirit and serenity, and green for rebirth and renewal which he embodied in his Torn Works. The white torn area of the composition is distinct in every piece, the viewer may decide for themselves what they see, but knowing my brother, it is a rip into space, representing a portal into another dimension in time.

In 1968 when 2001: A Space Odyssey opened at the theatres. The film touched something primal in Ching which was never forgotten. One cannot help but notice the similarity in the rectangular form that appears in the majority of his torn works. They resemble the film’s monolith which had the capabilities of time travel.

It has been said by those who knew Ching, that he was ahead of the era he lived in, the poet David Rattray once described Ching as a sage. These works transcend time, when I ponder his Torn Works, I have no choice but to wonder about another realm in our universe.

Certainty of Blue, 1985 Charcoal, pastel and graphite on paper. 50 x 38”

Untitled, 1984 Torn Works Series Charcoal, pastel and graphite on paper. 42 x 50”

It was on a trip to Turkey in 1981 that Ching discovered the stunning Turkish grottos. What was to follow, was to be his last series, the Alchemical Works. He found the caves to be utterly sublime and wanted to recreate this natural phenomenon in his artwork. He was impressed with the beauty and sustainability of the caves over hundreds of years. With a great deal of research and practice, Ching was able to replicate these incredible grottos in his studio at the Chelsea Hotel. His Alchemical Works were created by using iron oxide and gesso on paper. They were naturally processed to generate rust and texture by soaking the work in a man-made pool that the hotel allowed him to construct. These torn rust pieces marinated over a period of weeks until they became three dimensional and sculptural. This would be Ching’s final master work, “The Grotto,” a huge arc 10 feet tall that spans a length of 25 feet. It is magnificent and monumental. It seems quite fitting that this would be Ching’s last master work before he died, for as Ching said, “these paintings are intimations of the “miraculous”. The meaning is for the beholder to discover…

Ching Ho Cheng viewing his Grotto at the NYU Grey Art Gallery, 1987. 10 x 25”

Sybao Cheng-Wilson

Rev. April 2024