BRES Magazine "Visualizing The Invisible: The Psychorealism of CHING HO CHENG"

By David Rattray

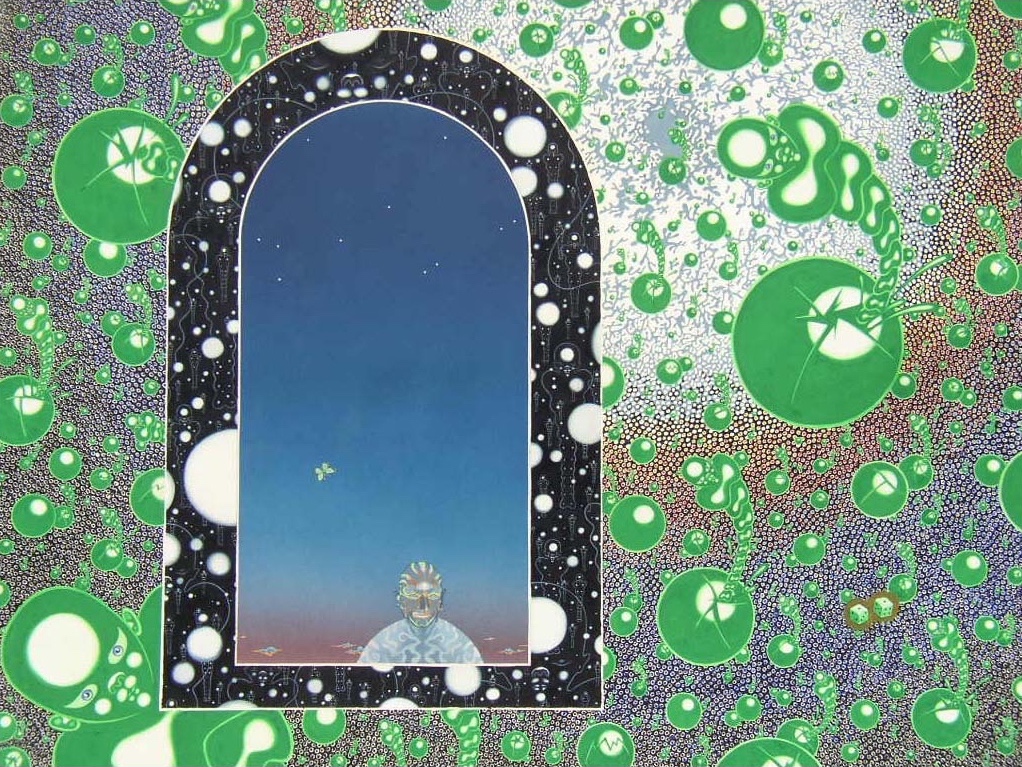

“The Astral Theatre” 1972. Gouache and ink on rag board. 30 x 38 1/2"

CHING HO CHENG was born in 1946 in Havana and, subsequent to his father's retirement from the foreign service of the Republic of China in 1949, educated in New York, where he studied at the Cooper Union School of Fine Arts. Although a lifelong New Yorker, he enjoys neither U.S. nor Chinese citizenship but is a "stateless person." In recent years he has exhibited in New York, Paris, Basel, and Amsterdam.

When one enters a room and comes face to face with a CHING HO CHENG picture, one's first impression is of a startling slash of energy, hot sensuousness, and surface glow. Simultaneously there is a feeling of balance and symmetry, of elegantly contained movement, tension, and flux. His pictures make a decorative first impression. But then, as one focuses on their disturbingly visceral imagery and funky sexuality, they get tough. The pictures are enclosed in plexiglass boxes rather than frames, so that the painted surface is continuous with the beholder's own space, thus implying that the confrontation between picture and beholder is an immediate one. Moreover, these paintings compel attention; one may either give oneself, or get out. The beholder who surrenders to the pictures' spell soon finds himself turned in, as it were, to an energy band that allows him to walk around inside their patterns. The painted surface will thus have functioned like the mirror in Through the Looking-Glass.

From the outset, CHING HO CHENG's work has been concerned with the visualization of certain grand themes: the coming into being of the cosmos; the origin of life, both in general and in particular; and that analogous psychic event referred to in Vedantic literature as the opening of the third eye: "My work all says the same thing; I only keep trying to say it in a new way, a way it was never said before. None of it is really new, however; they've said it again and again, and it's as old as the hills. All I can claim is that mine is a way of seeing I've never encountered anywhere else. I hate rehashes of the traditional ichnographies; the Tibetan, the Hopi, or the Navaho, for example, since all of these have been rendered with infinitely greater honesty (and better technique) by the native practitioners themselves." An early source of inspiration was HIERONYMUS BOSCH. This Chinese-American accepts the thesis that BOSCH's major works were originally made for mediational viewing by members of a mysterious secret congregation to which BOSCH himself belonged. Of BOSCH's pictures CHING HO CHENG says he admires their passion, the freedom and crudeness of their execution, and their effectiveness as vehicles for meditation. The Dutch master's freewheeling capriccios also provide the earliest demonstration that it is possible for a "modern" (as against, say, a Tantric) to communicate visions of magical reality via a self-created vocabulary of forms. The example gave the younger artist his initial point of departure, in 1969.

Cube consciousness

At the time he was at work on a series of boxes, each painted blood-red and stippled with hundreds of white dots, like a "car-crusher" fantasy: many corpses pressed into neat cubes. A physician viewing one of these early works remarked that CHING HO CHENG would make a fine medical painter. A year or so later, the blood-and-bone cube was to reemerge as the central image in "Angel Head"(1971), not as dead meat but as the shining stuff of life itself.

"Angel Head," 1971. Gouache and ink on rag board. 30 X 40”

The insight that life and death are one had already come to the artist during the months preceding "Angel Head"--via mescaline. In "Sun Drawing" (1970) the sun is depicted as a monstrous head haloed in crackling flames, its face crawling with worms, its blackened teeth bared, staring at the beholder out of a space teeming with microscopic cells, visceral tissues, and gigantic caterpillars--a juxtaposition of scale familiar in psychedelic perception.

"Sun Drawing," 1970. Marker and ink on rag board. 22 X 20”

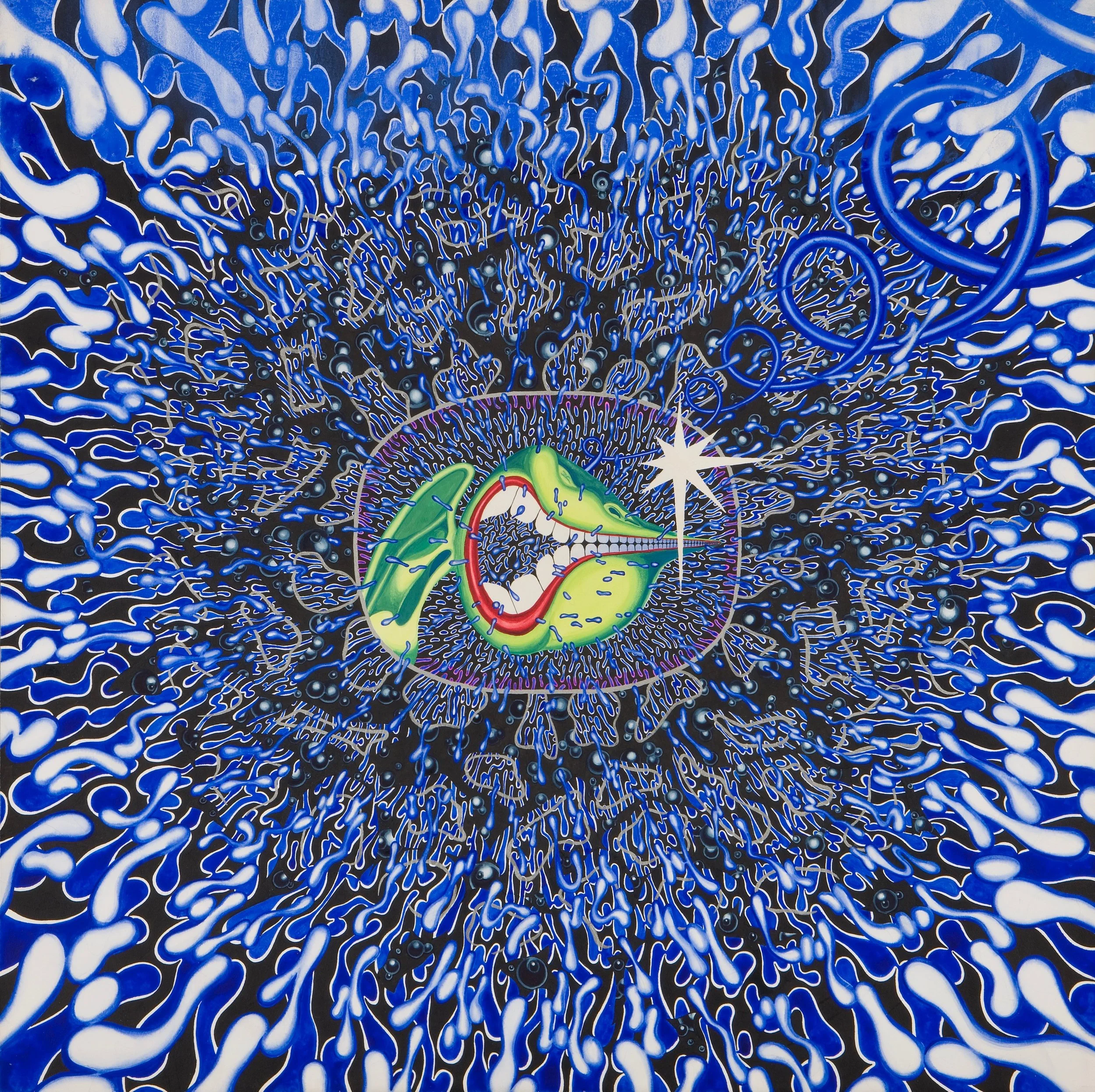

Closely related are "Glossolalia"(1970) and "Kiss"(1971). The earlier of the two is a nightmare vision of an infinitely elongated mouth amid an explosion of silvery eggs. As JOHN BARTH put it: "The speakers-in-tongues enounce atrocious tidings." Horror gives way to black humor in "Kiss," in which a half-dozen disembodied mouths grin over a maelstrom of spermy blue droplets. The dream of oneness and liberation through sexual rapture is at best problematical--a bit like the Cheshire cat's grin. An ectoplasmic being in the foreground of the picture sinks its teeth into an obelisk-shaped phallus that is plunged to its marrow-red root in the being's throat.

"Glossolalia," 1970. Gouache on rag board. 30 x 30"

"Kiss," 1971. Gouache on rag board. 25 X 25”

The phallic obelisk reappears, now pure gold, is the first (left-hand) panel of "X Triptych"(1971), in a synchronic representation of the moments of orgasm and conception. The center panel of the triptych is a complex mandala at whose center a fetus--rendered with photographic fidelity--curls inside a bubble through which one may glimpse a night sky full of stars. The composition's visual rhythm if expansive, an outward-moving spiral, very like that of the Whirlpool Galaxy in Canes Venatici. The right-hand panel of "X Triptych" depicts the sudden emergence from a cocoonlike caul (which opens like a ruff) of an extraordinary slant-eyed goblin with a "third eye" gleaming on his brow like a miner's headlight. As has often been remarked, the newborn look like visitors from outer space.

"X Triptych," 1971. Gouache and ink on rag board. Triptych, center panel. 30 x 30"

The cosmic spiral

The following year witnessed completion of a new triptych, "Queenie"(1971-72), in which the space-baby motif has been startlingly transformed into a Medusa with disheveled red hair, a tattoo in the form of a mustache around her mouth, and a spotlight glaring from her forehead.

"Queenie," 1971-72. Gouache on rag board. Triptych, center panel. 30 X 30”

The outside panels of the "Queenie" triptych, left and right, are predominately red and blue, corresponding to births by day and night respectively, and the Medusa head, emerging from a flowerlike ruff, is repeated over and over again.

The theme is process. The multiple-Medusa image stands for "felt" time, space, and change, which, in our perception of them, grow as if by buds or drops or other finite units bursting into being at a stroke, like an un-ending succession of heartbeats. In the triptych's center panel the multiple image zooms into a composite blowup of hypnotic force, "Queenie," whose all-important feature is motion, the passionate flow swirling into the center of the composition. The beholder's eye is drawn, clockwise, from the outside inward to the center. It is like looking into a huge cone. The kinematic mechanism that makes this composition work is analogous to the underlying dharma (motion-principle) pictures, which according to Tantric theory "have the function of enabling soul and matter to move or cause to move..." (AJIT MOOKERJEE). The illusion of rapid circular motion is created and, if the composition is successful, the beholder experiences a feeling of giddiness as if he were whirling. His head swims.

It would be a curious experiment to construct a cylindrical mirror in which to view "Queenie." When a true dharma picture is thus viewed, a mirage effect like that created by laser convergence in holography appears inside the cylinder, and as the beholder's eyes focus on it, the swirling image comes to rest. The spiral in "Queenie" is described by a succession of seven images, one inside the other, of the Medusa figure transforming into a fox. Each of these concentric figures marks a 60 degree clockwise displacement relative to the figure enclosing it. Each of the figures has a "third eye," coming full circle at the center, where the vixen's third eye is placed at the spot exactly corresponding to the largest, outermost figure's navel.

The symbolism of the woman-to-fox metamorphosis is to be understood in the context of the artist's mixed Chinese-American heritage. In 1940's U.S. slang, the word foxy meant "sexy." CHING HO CHENG's work abounds in sexual references, starting with his first--the cubes. (In Chinese symbology, cube=female, cone=male.) It is also a common place that according to Taoist tradition, the sex act represents life and light at their zenith and that images of it ward off darkness and death. Also, a woman nourishes not only her offspring but her mate, who during coitus absorbs her vital force. She is a citadel of strength. Sex is good for the mind and the body. (In this, the Taoists anticipated WILHELM REICH by 3,000 years.) The cells, sperm, and eggs that swarm in CHING HO CHENG's pictures amount to an organic (one might say, alchemical) conception of space itself, a concept also informing the Thousand-Buddha motif so often seen in the religious painting of various Eastern traditions. The Fox: In Chinese folklore, the fox has the power of self-transformation and most often transforms into a woman. The fox is also capable of creating mirages, knows how to make the Elixir of Life, is the only animal to salute the rising sun, and serves as a mirror to men's thoughts. The fox corresponds to our sexual, animal nature; the woman to the great mother, queen of Heaven, queen of illusion, creator and destroyer of all things. Some physicists consider that the best structural-dynamic description of the shape of the universe as a whole is a spiral. It is certainly the shape of most galaxies, and their motion; whether expanding or contracting back toward the center, galaxies describe a spiral path.* CHING HO CHENG's image of the world--like that of M.H.J. SCHOENMAEKER--is of "an exact beauty," and like the Dutch philosopher, the painter would "reduce the relativity of natural facts to the absolute, in order to recover the absolute in natural facts."

In the years since "Queenie" he has gradually moved away from the spectacular BOSCH-like capriccios of his original manner. He says: "I have had all my explosions. Now I must learn subtlety."

*As ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY once wrote: "The path to the center of the desert is a spiral."

Bres Magazine Vol. 61 November/December 1976